Deeper Than the Headlines: The OIG Uncovered Deficiencies in Ambulatory Surgery Centers

compliance, OIG, medicare, CMS, deeper than the headlines, compliance news, OIG Review, Surgery, Ambulatory, Ambulatory Surgery Centers, ASC, medicare payments, CfC

Medicare beneficiaries are increasingly using Ambulatory Surgery Centers (ASCs) for outpatient surgical procedures. In fact, Medicare payments to ASCs increased from $3.4 billion in 2011 to $4.6 billion in 2017.

To participate in Medicare, ASCs must demonstrate that they meet Medicare’s minimum requirements. Mos, known as “nondeemed ASCs,” undergo a State agency survey to do so. The others, known as deemed ASCs, are accredited by a Medicare-approved accreditor. CMS has established baseline health and safety requirements, called Medicare Conditions for Coverage (CfCs), that ASCs must meet to be eligible for participation in Medicare. The 14 CfCs cover topics ranging from credentialing and privileging of surgeons, to infection control and ASCs’ quality improvement programs. Each CfC covers a broad area (e.g., surgical services or infection control) and then is further defined by a set of specific standards that ASCs must meet.

Previously, the OIG assessed the frequency of ASC State certification surveys way back in 2002. They found that nearly a third of nondeemed ASCs had gone 5 or more years without a survey. Since that time, outbreaks of healthcare-associated infections have raised concerns about patient health and safety at ASCs according to the OIG.

Additionally, because ASCs often perform complex medical procedures, including invasive surgeries under general anesthesia, the OIG wanted to examine how Medicare ensures that ASCs meet minimum health and safety requirements through its State survey process. States also conduct investigations of complaints that allege poor care or other problems at ASCs. When a State conducts a certification survey, it may find that an ASC does not meet one or more requirements. If the State finds the ASC is out of compliance, it must determine whether the lack of compliance is at the standard level (less serious) or the condition level (more serious) by considering how serious the deficiency is in terms of its potential–or actual–harm to patients, and the extent of noncompliance. If the State finds that substantial noncompliance with multiple standards of a CfC adds up to pervasive noncompliance, or if it determines that noncompliance with one or more standards poses a serious threat to patient health and safety, it will cite the ASC with a condition-level deficiency. In instances of noncompliance, the offending ASC must submit a plan to achieve compliance for each cited deficiency.

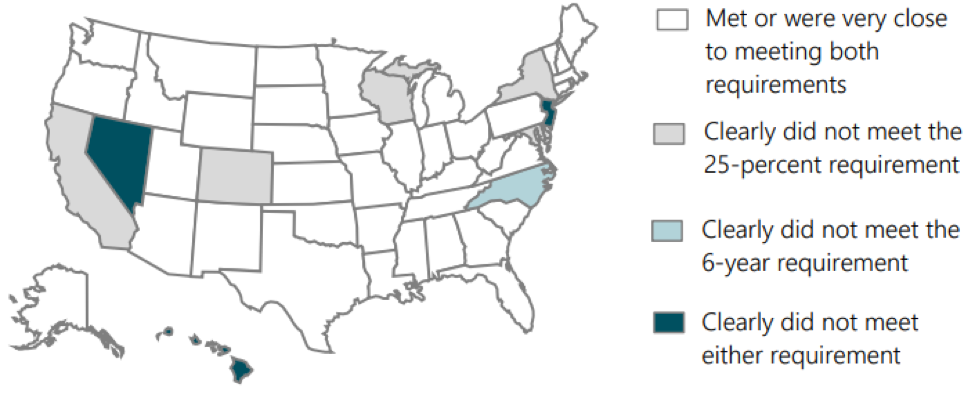

The most recent OIG review found that states by and large met Medicare’s requirements to survey 25 percent of nondeemed ASCs in fiscal year 2017. And nearly half of states met Medicare’s requirement to have surveyed all ASCs within the prior 6 years. However, some states fell short.

The OIG also found that states cited 77 percent of nondeemed ASCs with at least one deficiency, while one-quarter of ASCs had serious deficiencies. From 2013 to 2017, infection control deficiencies were the most frequently cited category of deficiency, making up about a fifth of all deficiencies. According to the OIG, ASCs appear to struggle with maintaining compliance with infection control requirements. In the most recent survey, states cited more than half (55 percent) of all nondeemed ASCs with one or more infection control deficiencies (e.g., failure to ensure that surgical equipment is sanitized properly.) It’s also of note that States cited ASCs with infection control deficiencies more frequently than other kinds of deficiencies. States also receive complaints regarding individual ASCs. The OIG review found that from 2013 through 2017, states received complaints for fewer than 4 percent of ASCs each year. However, the share of those complaints that required an onsite survey more than tripled over that time.

The OIG did draw some conclusions from its review. They felt that CMS, which oversees ASCs, has made progress in strengthening oversight of ASCs and addressing vulnerabilities that the OIG had previously identified. They also concluded that there was still more to be done. The results of this new analysis can support CMS in further strengthening its oversight, particularly of the few states that are falling short of meeting its requirements. It can also help CMS focus on ASCs’ recurring challenges in meeting health and safety requirements, especially for infection control.

Does your compliance program have any oversight or interaction with ASCs? If it does, then you’ll want to pay close attention to the recently published report on ASC oversight, which you can find here.

Questions or Comments?